Finding and Honoring Sonny Boy

by Nancy Robertson Beyer

|

Sonny Boy. That was the only name my dad had for his oldest brother who died at age two the year before Dad was born. Sonny Boy was the first child born to Oscar (O.B.) Robertson and Jimmie Deal. Four more sons would be born to them, but only the second born overlapped with Sonny Boy, and that by only three months.

Having lost both of his parents by age six, Dad held tightly to family memories. He treasured the few photos he had of Sonny Boy. He told how Sonny Boy died of pneumonia and was buried in an unmarked grave next to his father in West Point, Mississippi. The family story is that the Robertsons and Deals didn't approve of the union between Oscar and Jimmie, and the first child born to them was not accepted. But Sonny Boy sounds like a term of endearment to me. Perhaps they simply could not afford a marker. Somewhere along the way in my genealogical journey I decided to see if I could unravel the mystery behind Sonny Boy. I don't recall all of the steps I took, but I vividly remember phoning my dad when I had a copy of Sonny Boy's birth and death certificates in my hands. Dad's brother was William James Robertson. He was named after his two grandfathers, William Harrison Robertson and James Staughton Deal. The death certificate revealed William James died of dysentery on December 6, 1922. |

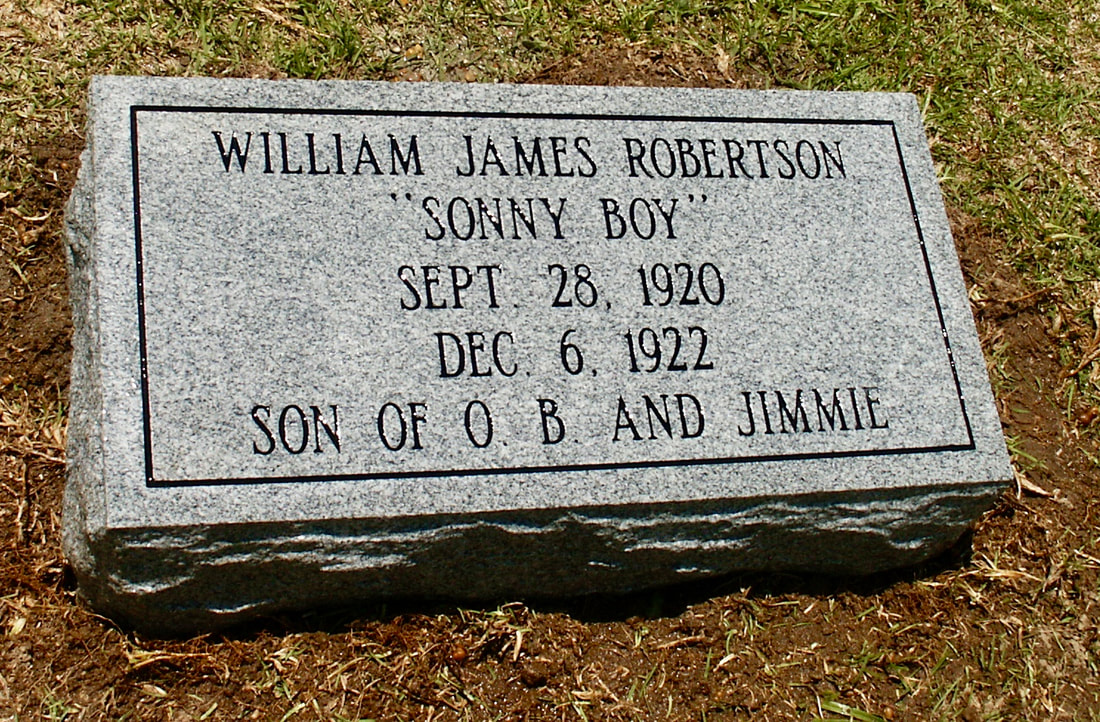

Before I visited Dad in Louisiana in 2006, I suggested we attempt to confirm Sonny Boy's burial place and add a grave marker. Dad was on board from the start. I contacted a funeral home in West Point where Dad's father is buried and discussed the plan. We ordered a stone with the following inscription:

William James Robertson

Sep. 28, 1920

Dec. 6, 1922

Son of O.B. and Jimmie

Sep. 28, 1920

Dec. 6, 1922

Son of O.B. and Jimmie

Dad and I stopped to visit an aunt and cousin on our way to West Point. We decided to keep our plans for the marker to ourselves, but somehow the conversation turned to Sonny Boy. I mentioned having discovered his real name, and my cousin replied that he would always be Sonny Boy to him. My heart sank. Was it too late to add "Sonny Boy" to the marker? Once back on the road we called and were told it probably was.

|

When we arrived in West Point a few days later we were met at the cemetery by Scotty from the funeral home. There we had our first experience with grave dowsing. The cemetery didn't have complete records, but Scotty said he would be able to tell if a child was buried next to Dad's father. Holding two rods, Scotty first demonstrated the technique by slowly walking over a marked grave. The rods crossed over him when he reached the beginning of the grave, then returned to their outward position when he reached the opposite end. I held my breath as Scotty was ready to check for a grave next to Oscar. I had no Plan B, and a marker was about to be delivered. The dowsing rods not only confirmed there was a grave, but based on the distance from one end to the other, that it was a child's grave.

|

Grave dowsing cannot give you the name of a person buried in an unmarked grave. But since the dowser found an unmarked child's grave right where we have been told Sonny Boy was buried--next to his father--we feel confident that it is his grave.

Dad and I both held our breath when the marker was delivered. We were over the moon excited when we saw the stone, complete with the nickname "Sonny Boy."

Dad and I both held our breath when the marker was delivered. We were over the moon excited when we saw the stone, complete with the nickname "Sonny Boy."

I think finding and marking Sonny Boy's grave will always be one of my more emotional genealogical experiences. And future Robertson descendants now have a tangible reminder of Sonny Boy's short life.

Published in the February 2018 issue of the KCGS Newsletter.